When Theodor Seuss Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) stepped into an elevator in 1955 on his way to a meeting with his publisher, Houghton Mifflin, he encountered Annie Williams, the elevator operator. She was “an elegant, and petite woman who wore white gloves and a secret smile”.[1] Ms. Williams would later serve as the inspiration behind the Cat in the Hat, so much so that when Dr. Seuss sketched the Cat in the Hat, “he gave him Ms. Williams white gloves, her sly smile and her color”.[2]

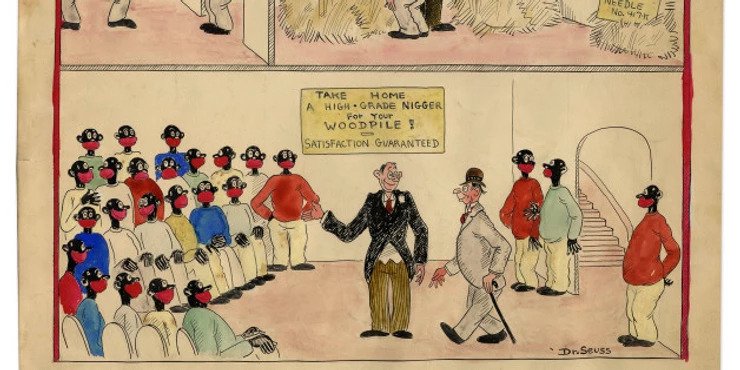

In his book, Was the Cat in the Hat Black, Philip Nel describes how “The Cat in the Hat is thus racially complicated, inspired by blackface performance, racist images in popular culture, and at least one real African American.” Other writers who have studied blackface minstrelsy contend that the Cat was also influenced by actual blackface minstrelsy, as evidenced in the Cat’s physical appearance, and the role he plays.

The Cat in the Hat as blackface was certainly not the image I had when I read the story to my toddler every night. My daughter adored The Cat in the Hat so much so that by the time she was two she had memorized every line, and could recite the book in its entirety. Nor do I think it was the image Michelle Obama had in her mind when she read The Cat in the Hat, what she described as “one of our favourite books” to various crowds of children, including to a group of children in Johannesburg.

Most of us are oblivious to the presence of blackface and other racist imagery in Dr. Seuss books. The subtle way in which blackface has been woven into popular culture is precisely why we need to confront its insidious history as part of a deeper discussion around racism, privilege and cultural appropriation. It is a teachable opportunity for educators and parents alike to begin these uncomfortable conversations and the learning journey of why blackface is much more than just white skin and dark makeup.

American blackface has its origins in minstrelsy, when white performers would darken their faces to imitate and mimic African slaves. These performances “characterized blacks as lazy, ignorant, superstitious, hypersexual, and prone to thievery and cowardice.” According to Ishizuka and Stephens, “This racist tradition is embodied by the Cat, and is ultimately sustained and carried on through this book.”

Blackface has been a large part of American culture, reinforcing and entrenching racial stereotypes of Black people. Jim Crow, which established legalized segregation in the United States, was a blackface minstrel character performed by a popular white entertainer, Thomas Dartmouth Rice. Rice would darken his face, “acted like a buffoon, and spoke with an exaggerated and distorted imitation of African American Vernacular English.” Canada itself has not been immune from blackface. Around 1840, American circuses would travel to Toronto, where white clowns donned blackface. For four years, Black Torontonians unsuccessfully petitioned Toronto’s city council to prohibit the blackface performers on the grounds that they “make the Coloured man appear ridiculous and contemptible in the eyes of their audience.” Blackface is present throughout Canadian history. Even Quebec musician Calixa Lavallée, who composed the national anthem, “O Canada”, is reported to have travelled as a blackface minstrel.

The history of blackface is clearly lost on those who parade around at Halloween, during school concerts, and costume parties in blackface. It betrays the racist history of minstrelsy that entrenched racial stereotypes, humiliated Black people and exploited the Black identity.

So how do we talk to our children about blackface?

How do we unpack the layered history of blackface and present it as a teaching moment to our children and students? We first need to situate blackface as part of a long history of slavery, oppression and anti-Black racism. In order to do so, we first need to have an awareness about racism and how we enable systems of oppression to persist, even today. This is an uncomfortable awareness that we must sit with because it requires us to challenge narratives and ideas that are deeply entrenched in our mindset and within society. What does it mean that characters like Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, the Cat in the Hat and other beloved characters had their origins in a dark, racist history? We need to sit with the discomfort of challenging what we have accepted as part of our cultural identity.

Awareness involves a process of self-reflection of our own biases, privileges and ideas that enable anti-Black racism to exist. Consider for a moment, as a parent or educator, how many people in your life you trust and who you hold within a close circle of confidants. Are these individuals Black or do they belong to other racialized identities? Do you expose yourself, your children or students to other cultural experiences? What books do you read to your children and students? How do images in those books depict Black identities?Blackface has become such an invisible part of our culture precisely because we continue to ignore systemic racism and the role we all play in enabling systems of oppression. Conversations about blackface must be contextual but also purposeful. A child cannot understand blackface without understanding its historical context.

We can begin conversations with our children and students about blackface by explaining its origins and its impact as a form of racial oppression. For instance, explaining to children what it means for a person to darken their face and the historical practice of white people donning blackface to ridicule, mock and degrade Black people. This can be an opportunity to explain inequality and the impact of such treatment on people’s emotions, their opportunities to succeed, and their sense of belonging within society.

We can also take the opportunity to examine how blackface is very much endemic in children’s literature, and challenge popular culture that honours these racist ideas. How do characters in the books we read, however innocuous they appear, represent a history of racism and bigotry? I have had to sit with that discomfort, thinking of the multiple times I read The Cat in the Hat to my children.

This does not necessarily mean we must immediately discard these books from our libraries and homes. Doing so denies the historical context that we need to confront. As Toni Morrison once observed, “The act of enforcing racelessness in literacy discourse is itself a racial act.”[3] We need to engage in meaningful conversations about these books. Parents and educators can ground their discussion around racial stereotyping and the implications of these stereotypes on all students. What harm ensues? What are the societal consequences of depicting Black people as lazy, inferior and ridiculing their identity?

The ubiquity of blackface in our society is a reminder that there is so much work we need to do to educate ourselves and our children about racism. We cannot teach what we do not know. We can learn by reading about the Black experience and anti-Black racism. Books like How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo, and Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do by Jennifer L Eberhardt, are excellent resources for understanding racism in North American society.

Children’s books are a window to the world. They are “one of the places that racism hides—and one of the best places to oppose it”.[4] Parents and educators can do so much to construct meaning around these images through an informed awareness about blackface and its history. The reason we say often and loudly that picture books can change the world is because they can, and we are here to help you select the books that lead to conversations that create a better world.

If you want to learn more about the history of Blackface in Canada, you can check out these resources:

The Complicated History of Canadian Blackface

The Problem With Blackface

[1]In Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books, Philip Nel, Oxford University Press, 2017, page 31.

[2]In Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books, Philip Nel, Oxford University Press, 2017, page 32.

[3]In Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books, Philip Nel, Oxford University Press, 2017, Page 67.

[4]In Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books, Philip Nel, Oxford University Press, 2017, Page 1.